Ancient genomes reveal more than two thousand years of dingo population structure

A leading Charles Sturt University researcher co-led a multi-discipline team investigating the origins of dingoes, when they arrived in Australia, and how they changed over nearly three thousand years.

First published by Charles Sturt University

- A Charles Sturt University researcher co-led an extensive genomic study of ancient dingoes to better understand their early history in Australia

- The research uses pre-European dingo specimens to confirm that modern dingoes derive little genomic ancestry from hybridisation with modern domestic dogs

- Appropriate dingo management and conservation depends on understanding their origins and population history

A leading Charles Sturt University researcher co-led a multi-discipline team investigating the origins of dingoes, when they arrived in Australia, and how they changed over nearly three thousand years.

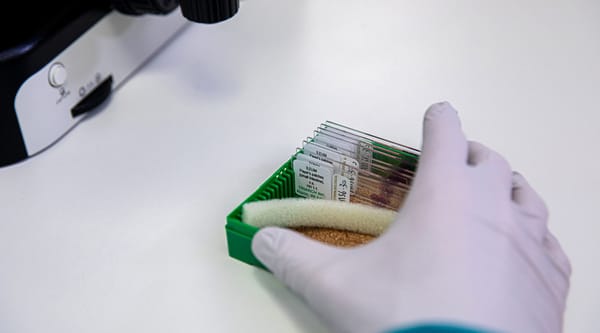

Professor of Evolution and Environmental Change Alan Cooper in the Charles Sturt University Gulbali Research Institute for Agriculture, Water and Environment analysed genomes from skeletons and mummies of dingoes found in the many caves of the giant Nullarbor Plain across southern Australia.

The collaboration involved dozens of scientists from universities in Australia and internationally, including Spain and New Zealand, and published their findings this week in a research paper, ‘Ancient genomes reveal over two thousand years of dingo population structure’, in the prestigious journal PNAS.

“Dingoes are culturally and ecologically important free-living dogs whose ancestors arrived in Australia over 3,000 years ago, transported by seafaring peoples,” Professor Cooper said.

“We examined genomic data from ancient dingo individuals, ranging from 400 to 2,746 years old, to reconstruct what dingo populations looked like prior to the introduction of modern domestic dogs into Australia and persecution by European colonisers.”

Professor Cooper said the early history of dingoes in Australia, including the number of founding populations and their routes of introduction, had been uncertain.

“Our results show that there appear to be two distinct populations, one covering north and western Australia, and the other Eastern Australia including the Alpine areas. This second group appears to have had genetic contact with the New Guinea singing dogs around 2,500 years ago, which is pretty interesting as humans had to be transporting them,” he said.

“It seems dingoes were introduced in a single phase, but the west versus eastern population structure observed in modern dingo populations had already emerged several thousand years ago.

“We can confirm that modern dingoes derive surprisingly little genomic ancestry from hybridisation with other domestic dog lineages, and instead descend primarily from ancient canids introduced to Australia and New Guinea thousands of years ago. They are critically important to conserve.”