Tasmanian devil declines impact quolls

A steep drop in the population of the endangered Tasmanian devil is creating knock-on effects to the evolutionary genetics of the spotted-tailed quoll, according to a new Nature Ecology & Evolution study.

First published by University of Tasmania

A steep drop in the population of the endangered Tasmanian devil is creating knock-on effects to the evolutionary genetics of the spotted-tailed quoll, according to a new Nature Ecology & Evolution study.

A global research team including experts from the University of Tasmania have found the decline of Tasmania’s top predator species, caused by a highly transmissible facial cancer, has enabled increased activity and less competition for quolls, the next level of predatory species in the ecosystem.

The team found these broad changes have also led to changes in the genetic make-up of the quolls.

Professor of Biological Sciences and marsupial carnivore expert from the University of Tasmania’s School of Natural Sciences, Menna Jones, said predator declines were occurring around the world, and they have cascading ecological effects.

“We can see the activity of the spotted-tail quoll has shifted significantly in the regions where Tasmanian devils have severely reduced numbers,” Professor Jones said.

“Spotted-tailed quolls have shifted their peak night-time activity, from pre-dawn to avoid devils, to early evening with low devils when most prey are active and hunting is the best.

“We found that with fewer devils – Tasmania’s top scavenger – quolls are benefiting from more carrion and are spending more time feeding at carcasses.”

The research team then set out to understand whether the changes to devil populations were changing evolutionary processes (the genes) in the quolls.

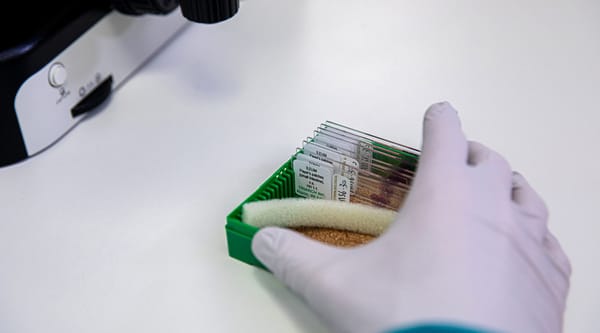

Over 15 years, the team collected genome marker data from 345 quolls across 15 generations, and looked for evidence of genetic variation and natural selection associated with differences in Devil Facial Tumour Disease (DFTD) prevalence and geographical location.

They found in areas where facial tumour disease was impacting the devil population, there was evidence of less movement of genes between quoll populations and more differences across geographically separated quoll populations in genes specifically related to muscle development, movement and feeding behaviour.

“It’s likely these genetic traits that appear to be shifting are involved in food competition between quolls and devils.

“There is less competition and more food, reducing the need for quolls to move around as much or as far as they once would have,” Professor Jones said.

“There’s also changing evolutionary pressure on physical performance associated with escaping from devils and fertility of the quoll populations as devil numbers decline.”

The research team hoped the “community landscape genomics” approach used in this study would be used more broadly to enable greater understanding of the evolutionary consequences of predator declines around the world.

Read this research paper in Nature Ecology & Evolution.