Submerged archaeology highlights protection

New archaeological research has highlighted major blind spots in Australia’s environmental management policies which are placing submerged Indigenous heritage at risk.

First published by Flinders University

New archaeological research has highlighted major blind spots in Australia’s environmental management policies which are placing submerged Indigenous heritage at risk.

New archaeological research has highlighted major blind spots in Australia’s environmental management policies which are placing submerged Indigenous heritage at risk.

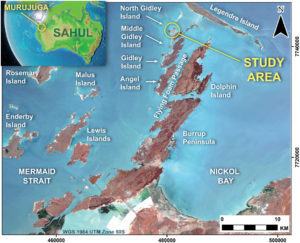

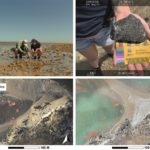

The Deep History of Sea Country (DHSC) project team have uncovered a new intertidal stone quarry and stone tool manufacturing site, as well as coastal rock art and engravings, during a survey off the Pilbara coastline in Western Australia.

The findings have been published alongside a separate study focused on the Northern Territory which identified underwater environments dating back to the Pleistocene that could provide important environmental and cultural insights into ancient Indigenous migration, land use and early occupation of Australia.

The findings, published in Australian Archaeology, outline the need for a national policy which ensures resource companies operate with care for Aboriginal heritage and develop protections against climate change, dredging, windfarms, interconnectors, and seabed mining while promoting industry collaboration with Indigenous stakeholders and archaeologists.

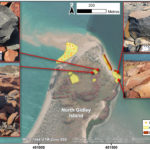

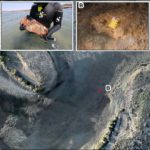

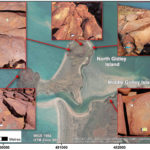

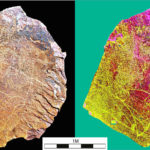

Aerial, landscape and ground surveys of North Gidley Island and Cape Bruguieres in Western Australia represent fresh evidence of cultural heritage where hundreds of submerged ancient stone tools made by Aboriginal people dating back to more than 7,000 years ago were discovered. The team is yet to determine the exact age of the sites found on the channel, but the results demonstrate a promising way forward to study the integrated landscape above and below the water line.

“The challenge we now face for Australian submerged heritage is to extend the discoveries made at Murujuga to other areas, both in the land and seascape around these sites, but also across the Australian continental shelf” says Associate Professor Jonathan Benjamin who is the Maritime Archaeology Program Coordinator at Flinders University’s College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences.

“We need to better understand and manage this underwater cultural heritage through local and national approaches. We must consider the very different scales of research, from ‘big data’ down to the boots-on-the-ground and snorkels-in-the-mouth as we comb Australia’s coasts, intertidal zones and submerged environments to record new archaeological sites. Submerged sites are highly likely to be discovered around the continent, and down to depths as great as 130 metres.”

An international team of archaeologists from Flinders University, The University of Western Australia, James Cook University, ARA – Airborne Research Australia and the University of York (United Kingdom) collaborated in partnership with the Murujuga Aboriginal Corporation to produce novel aerial and intertidal surveys of the cultural landscape in WA.

“We found evidence of a diverse range of cultural activities across North Gidley Island, including evidence of ancient seed processing, marine resource use, lithic quarrying & production, rock art production and ceremonial activities. Dating this range of activities remains challenging, but there is some indication from engravings and submerged material that North Gidley Island was occupied at the terminal Pleistocene and into the Holocene,” said lead author Jerem Leach, who recently completed his Masters Degree in Maritime Archaeology at Flinders.

In 2019, the dive team mapped 269 artefacts at Cape Bruguieres in shallow water at depths down to 2.4 metres below modern sea level. Radiocarbon dating and analysis of sea-level changes show the site is at least 7000 years old.

“Artefacts embedded in aeolianite provide an opportunity to understand the age of at least some of these stone artefacts, which could be supported by excavation both on land and in the more sheltered and sediment-rich intertidal zones north of the Cape Bruguieres channel,” says Distinguished Professor Sean Ulm from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, James Cook University, a co-author of the study.

“The Gidley Islands represent a continuous cultural landscape above and below that waterline that tell the story of people responding to climate change, a story that incorporates the re-negotiation of landscape use between maritime and arid coastal communities, much like we see with climate change today.”

“Rock art engravings, grinding patches, quarries and upstanding stones – some of which are in the intertidal zone – point to the to the possibility of discovering new underwater sites in WA, and around Australia.”

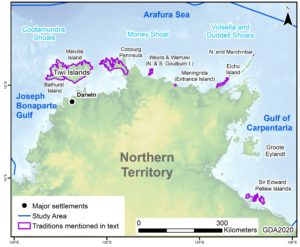

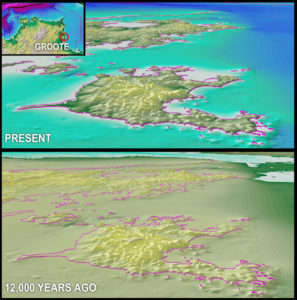

Dr John McCarthy says the area to the north of the Northern Territory coast contains the widest part of the continental shelf, in an area with special importance as it lay between Australia and New Guinea at the time of first peopling of the continent when these two landmasses were connected into a single landmass known as Sahul.

“We concluded that submerged landscapes around Darwin and Bynoe Harbours provide varied and partially sheltered environments with maximum availability of facilities to support fieldwork. More remote areas attractive for prospection include the Tiwi Islands, the Wessel Islands and within the Gulf of Carpentaria, Groote Eylandt and the Sir Edward Pellew Islands, where the focused energy of currents and tides may provide windows of opportunity through erosion of sediments.”

“Our Northern Territory study has highlighted a blind spot in marine management in this country. Submerged archaeological landscapes have not been included in nationally-coordinated studies on marine biology and shipwreck heritage. With this study we provide a template for state-level baseline studies to extend the search for submerged landscapes nationally.”

Dr McCarthy was also recently awarded an ARC Discovery Early Career Researcher Award to develop new machine learning tools to reduce the cost of the search for these submerged landscapes.

Scientists estimate there were 2 million square kilometres more coastal plain during the last Ice Age compared with today, and the larger coastal lands now forming Australia’s underwater continental shelf are expected to hold many significant archaeological sites.

The submerged cultural landscapes represent what is known today as Sea Country to many Indigenous Australians, who have a deep cultural, spiritual and historical connection to these underwater environments.

Murujuga Aboriginal Corporation CEO Peter Jeffries says the surveys add further weight to the importance of ensuring the community can add to the story of Aboriginal people in the Pilbara, and around Australia.

“It has confirmed our beliefs and stories about country, and helps explain where and how our people lived, and why they moved.

“Interestingly, the inscriptions and rock art depicting sea animals right on, or near, water now – would have been coastal living areas that was previously dry ground and safe for sleeping on. These areas are now right on the waters edges, or underwater, and non-habitable” said Mr Jeffries.

“For Australia and the world this is a fantastic find for us all to celebrate. We look forward to further investigations and research on our sea country and expect to find many more artefact deposits – in particular if our stories are anything to go by” he said.

Deep History of Sea Country Project with Murujuga Aboriginal Corporation