Partnering to solve the Pacific plastics plight

Microplastics are notoriously hard to detect but their impact is significant. How deep is the problem in the Pacific Ocean? Scientists from Australia and Samoa teamed up to find out.

First published by the University of Newcastle

By Penny Harnett

When Fimareti Tupu Selu was a child her Dad would take her snorkelling to explore the beautiful, colourful coral reefs surrounding their village in Samoa. Her connection to the ocean is deep – it’s a source of life for the people of Samoa who rely on it for food and income.

Fimareti grew up to become one of Samoa’s top marine scientists. She works in the Division of Environment and Conservation at the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment.

Her job brings her back to the same coral reefs she once snorkelled with her Dad. But Fimareti explains with a hint of a sadness “they look different now.”

“There is plastic everywhere. I see plastic bottles stuck in coral and wrappers floating next to fish,” Fimareti says.

Microplastics result from the breakdown of macroplastics – bottles, wrappers etc. They are particularly troublesome because they are hard to detect but pose great danger to marine life, the environment and human health.

Quantifying the extent of the plastic pollution problem is an unfair burden Pacific Island nations face because of the world’s obsession with plastic. The Pacific region contributes as little as 1.3 per cent of the world’s plastic pollution yet have the highest recorded quantity of floating plastics in the world.

The University of Newcastle’s Pacific Engagement Coordinator, Dr Sascha Fuller says plastic pollution is everyone’s problem.

“Around ninety per cent of plastics produced end up in our environment. A large proportion of this is in our oceans.

Did you know?

The term ‘large ocean small island developing nations’ has been adopted to overcome misconceptions that the Pacific Islands region is made up of small islands that are remote and insignificant, when in fact Pacific Island territories are very large - comprising mainly of ocean. For nations like Samoa, the ocean is integral to their identity and development.

“Large ocean small island developing nations, such as Samoa, are disproportionately impacted.

“Despite its known harms, the rate of toxic plastics production and consumption across the world is accelerating,” Dr Fuller says.

Fimareti was part of the team of Samoan scientists who worked alongside University of Newcastle scientists and students to collect microplastic samples in and around the island of Upolu during the two-week study.

“We’ve heard of microplastics. We’ve studied microplastics. But this is the first time we’ve actually identified the different microplastics that are infiltrating our beaches, mangroves and oceans,” Fimareti says.

Along with Samoa’s top marine scientists from Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment and the Scientific Research Organisation of Samoa, students from the National University of Samoa also participated in the sampling.

“The study also supports strategic priorities and themes in the Samoa Ocean Strategy,” Fimareti says.

The Samoa Ocean Strategy 2020-2030 is the national policy framework to sustainably manage Samoa’s vast ocean and marine resources for the well-being of Samoans now, and into the future. The Strategy highlights the need for integrated management solutions.

“It was a really great opportunity to learn a new methodology for gathering and sampling microplastics,” Fimareti says.

“This study aligns with the Strategy by improving scientific research, data collection and monitoring in Samoa’s Ocean. And it will help to improve waste and marine pollution management at a national level.”

"We really need this information to inform decision making."

In addition, the data collected will support Samoa by providing baseline figures to develop benchmarks, targets and goals for plastic reduction.

“We really need this information to inform decision making, and also come up with better ways to manage our waste,” Fimareti says.

Dangerously small

Microplastics are less than five millimetres in size – smaller than a grain of rice. It’s their insignificant size which makes them particularly dangerous to marine life and human health.

Dr Khay Fong who led the study from the University of Newcastle and Monash University says plankton and other small creatures unknowingly consume these tiny plastics.

“This can trigger an immune response which affects the health, growth and reproduction of these creatures. Ultimately, this would reduce sea life populations.

“Microplastics concentrate in the digestive tracts of small fish and bivalves like oysters. This has flow-on effects to predators up the food chain, including the fish humans eat,” Dr Fong explains.

Due to their small size, changed surface chemistry and large surface area, microplastics can attract and carry other toxic pollutants such as heavy metal and PFAS.

“So along with less fish to catch and eat, there would be greater risk of toxicity in those that remain. This is particularly concerning for Pacific Island people as seafood is a key element in their diet,” Dr Fong says.

Quantifying microplastics is a crucial step to better understand and manage microplastic pollution.

"We’ve seen microplastics in almost every sample."

“We don’t know much about microplastics in the Pacific. So, this study is really useful to set a baseline."

“The project started as the quantification of microplastics in the Pacific Ocean,” Dr Fong explains.

“But it developed into so much more than that.”

“It developed into a collaboration with Samoan scientists. Hopefully the data we collected together will provide evidence to inform global plastic pollution policy and plastic management in Samoa.

“So far, we’ve seen microplastics in almost every sample – in the beaches, mangroves and in the ocean.”

“We will continue working with our Samoan research partners to analyse the samples in the lab and publish our findings,” Dr Fong says.

Catching microplastics with a manta trawl

In beaches and mangrove areas, Dr Fong and the team used the AUSMAP method to sample a cubic metre of sand at four randomly selected intervals along a 100 metre transect.

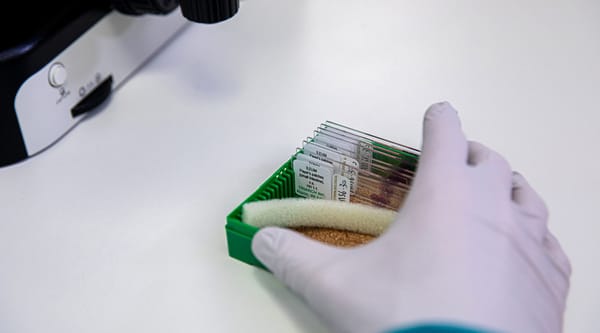

“We sieve the sand through two different size sieves – one that captures debris larger than five millimetres, and one with a smaller pore size of one millimetre. So, we’re capturing two size ranges of microplastics,” Dr Fong explains.

“Depending on their size, we can spot some microplastics visually. They have distinct shapes and are coloured differently from natural sand and shells.

“We then take all of our samples to the lab for further analysis.”

To sample the Pacific Ocean surrounding Upolu, the team cast a manta trawl net system from a boat. This method allowed thousands of litres of surface water to be sampled at each survey site.

Dr Fong and her research partner, Dr Roman Lehner from Sail and Explore Association, modified the manta trawl so that it could capture smaller sized microplastics, which until now have not been scientifically documented in the Pacific Ocean.

“A lot of data has been captured around the world on microplastics in the ocean but most of these studies are looking at microplastics larger than 300 microns in size.

“We’ve added a second net with a much smaller pore size to our manta trawl. This is the first time in the Pacific Ocean that much smaller microplastics down to 50 microns have been captured and documented.”

A once-in-a-lifetime experience

Thanks to the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade-funded New Colombo Plan program, eight University of Newcastle students participated in the two-week microplastics study in Samoa. They worked alongside Samoa’s top scientists and students from National University of Samoa.

“I never imagined I would get to be part of something like this at University.”

From staying in traditional Samoan fales mere steps from the ocean to enjoying their daily fish catches for dinner, the students experienced the best of Samoan culture while undertaking their field work.

University of Newcastle student Campbell Martin says the experience was one he will never forget.

“One of the reasons I chose to study at the University was because of their values for sustainability.

“It’s great to see the relationship that the University has with the Pacific Islands and how they genuinely care,” Campbell says.

Strengthening ties in the Pacific

During the study tour, the team of University of Newcastle researchers and students visited the Australian High Commission in Samoa. For Campbell, who is a Development Studies student, it opened his eyes to a world of career possibilities.

“It was an incredible opportunity.

“We met with the Acting High Commissioner of Australia to Samoa and learnt about the programs in place to support the partnership between Australia and Samoa.”

The University of Newcastle has long strived to forge strong research and capacity development partnerships in the Pacific.

“This was not a fly-in, fly-out project for our University” ~ Dr Fuller

In fact, the University of Newcastle has been building a relationship with the Pacific since 2017.

The University established a Pacific Node in Apia, Samoa – an initiative of one of its flagship research institutes, the Newcastle Institute for Energy and Resources (NIER), in partnership with the Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP).

The Node aims to deliver meaningful research impact and enhance regional capability through collaboration in the Pacific.

Recognising the importance of partnership, Dr Fuller explains plastic production by the world’s biggest plastic polluters must be reduced.

“The plastics pollution problem in the Pacific is everyone’s problem.

“We all have a role to play in solving it.”

Fimareti says the project has been good capacity building to bring Samoa one step closer to better plastic management.

“I want our children to walk on sandy beaches and not plastic polluted beaches.

“I am very grateful for this partnership where we get to collaborate with the University of Newcastle,” Fimareti says.

This project was delivered in partnership with the Scientific Research Organisation of Samoa (SROS), Samoa’s Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, the Secretariat of the Pacific Environment Program (SPREP), the National University of Samoa (NUS), and Sail and Explore Association (Switzerland).