How genetically modified flies can reduce waste and keep it out of landfills

Black soldier flies which are currently commercially used to consume organic waste will now be able to tackle a wider variety of refuse thanks to genetic modifications devised by Macquarie University bioscientists.

First published by Macquarie University

A Macquarie University team proposes using genetically engineered black soldier flies (Hermetia illucens) to address worldwide pollution challenges and produce valuable raw materials for industry, including the US$500 billion global animal feed market.

In a new paper published in the journal Communications Biology, scientists at Macquarie University outline a future where engineered flies could transform waste management and sustainable biomanufacturing, addressing multiple United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

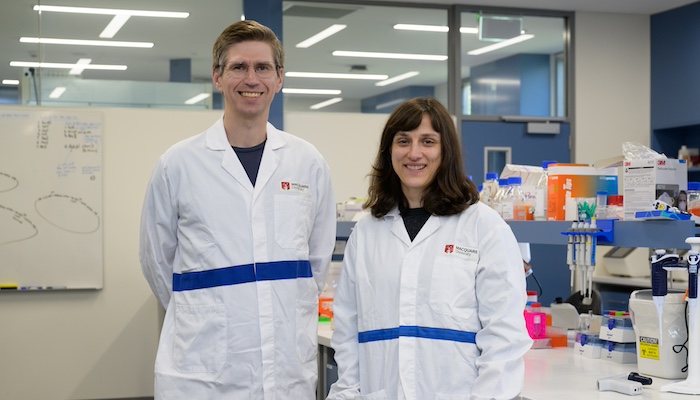

Synthetic biologist Dr Kate Tepper is lead author of the paper and a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Applied BioSciences, Macquarie University.

“One of the great challenges in developing circular economies is making high-value products that can be produced from waste,” says Dr Tepper.

Landfill Emitters

An estimated 40 to 70 per cent of global organic waste finds its way to landfills.

“The landfilling of organic waste creates about five per cent of annual global greenhouse gas emissions and we need to get this to zero per cent,” Dr Tepper says.

Organic by-products from sewage treatment – municipal biosolids – can be used as an alternative to synthetic fertiliser to grow crops and close nutrient cycles.

Insects will be the next frontier for synthetic biology applications, dealing with some of the huge waste-management challenges we haven’t been able to solve with microbes.

However, Dr Tepper notes there are rising concerns about toxic chemicals in waste, including dangerous ‘forever chemicals’ such as per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

Black soldier flies are already valued in waste management where they consume commercial organic waste before being processed as ‘insect biomass’ into foods for domestic pets and for commercial chicken and fish farmers.

But the Macquarie team believes genetic engineering could extend the usefulness of the black soldier fly, enabling them to turn waste inputs into enhanced animal feeds or valuable industrial raw materials.

Engineering insects to make industrial enzymes and lipids that are not used in food supply chains will expand the types of organic wastes that can be used, which adds utility to lower-grade organic wastes.

Senior author Dr Maciej Maselko, who heads an animal synthetic biology lab at Macquarie University’s Applied BioSciences, says: “Insects will be the next frontier for synthetic biology applications, dealing with some of the huge waste-management challenges we haven’t been able to solve with microbes.”

Genetically engineered microbes require sterile environments to prevent contamination, along with lots of water and refined nutrient inputs.

“We can feed black soldier flies straight, dirty trash rather than sterilised or thoroughly pre-processed [trash]. When it is just chopped into smaller pieces, black soldier flies will consume large volumes of waste a lot faster than microbes,” Dr Maselko says.

The researchers suggest genetic engineering could piggyback on the existing infrastructure for large-scale black soldier fly farming, elevating the flies from simple waste processors to high-tech biomanufacturing platforms. In the paper, the researchers outline a roadmap calling for better genetic engineering tools for key insects.

“Physical containment is part of a series of protections. We are also developing additional layers of genetic containment so that any escapees can’t reproduce or survive in the wild,” Dr Maselko says.

Commercialisation of black soldier fly biomanufacturing is already underway through a Macquarie University spin-out company, EntoZyme.

Dr Tepper says that the introduction of genetically engineered insects has potential, not just in the multi-billion-dollar waste management market, but also in the production of a range of high-value industrial inputs.

“If we want a sustainable circular economy, the economics of that have to work,” says Dr Tepper.

“When there is an economic incentive to implement sustainable technologies, such as engineering insects to get more value from waste products, that will help to drive this transition more rapidly.”