Fight for justice

The fight to free Kathleen Folbigg – the woman once dubbed Australia’s worst female serial killer – started in 2013 with the University’s Legal Centre and its law students helping to drive the movement.

First published by the University of Newcastle

By Carmen Swadling

“Today is a victory for science and especially truth … and for the last 20 years I have been in prison, I have forever and will always think of my children, grieve for my children and miss and love them terribly.” – Kathleen Folbigg

Their names were Caleb, Patrick, Sarah and Laura.

When they died in the NSW Hunter Valley between 1989 and 1999 they were aged 19 days, 8 months, 10 months and 18 months.

Their mother, Kathleen Folbigg, served more than two decades behind bars, convicted of their murders and manslaughter.

But she always denied harming them.

On Monday 5 June, 2023, 56-year-old Kathleen walked free from prison, unconditionally pardoned by NSW Attorney General Michael Daley, after preliminary findings of a second landmark inquiry gave rise to reasonable doubt as to her guilt.

“I’m extremely humbled and extremely grateful for being pardoned and released from prison,” Kathleen said in a video message released by her team.

Smiling, seemingly relaxed, yet noticeably aged and worn from the years of anguish and unbearable pain of having lost four children, Kathleen expressed heartfelt appreciation for her supporters.

“My eternal gratitude goes to my friends and family - especially Tracy (Chapman) and all her family; and I would not have survived this whole ordeal without them.”

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by Sarah Harris (@whatsarahsnapped)

David versus Goliath battle

Kathleen’s path to freedom was long, arduous and fought in a David and Goliath-type battle to seek a fair system of law and due process.

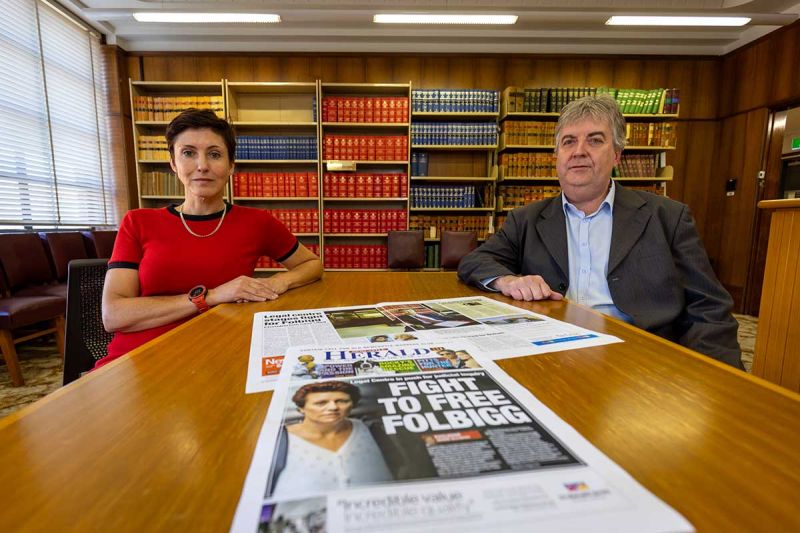

A Newcastle team of barristers, academics and law students was integral to the fight. *

With a proud tradition of taking on high profile public interest cases and supporting marginalised people in accessing the legal system, the University of Newcastle Legal Centre identified Kathleen’s case as one it could support.

In 2013 the Legal Centre announced it would seek a judicial review of the case, in collaboration with three Newcastle barristers, providing unpaid support to build the submission.

At the time of the announcement, the Legal Centre’s Director, Associate Professor Shaun McCarthy, suggested the case “may well have parallels with the Lindy Chamberlain case.”

‘‘It really goes to the heart of the rule of law,” he told the Newcastle Herald in October 2013.

"The Legal Centre takes the view it’s the human right of every person to have their day in court if there is fresh evidence which casts doubt over the original convictions."

Murder, Medicine and Motherhood

That escalating doubt about Kathleen’s 2003 convictions gained significant support after the publication of a thesis and book in 2011 titled Murder, Medicine and Motherhood by law academic Emma Cunliffe.

In it, the Australian-born and Canadian-based author raised serious concerns about whether Kathleen’s trial was fair - and ultimately - whether there was a serious miscarriage of justice.

Sentenced to 40 years in prison with a 30-year non-parole period, it was later reduced on appeal to 25 years non-parole.

In face-to-face meetings at Sydney’s maximum security Silverwater Correctional Complex to obtain instructions from Kathleen, Shaun, who was her instructing solicitor from 2013 to 2017, said Kathleen felt the legal system had not served her well.

"I think Ms Folbigg had a lot of gratitude that we had taken an interest in the case, that someone was listening to the problems," Shaun said.

“However, she wanted to make sure we were going to follow through with the case and that it wasn't just an academic interest."

The commitment to the case was never in question.

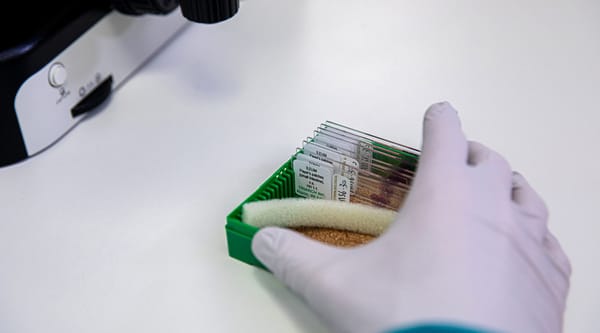

Under expert supervision, large numbers of law students reviewed trial transcripts, researched similar wrongful conviction cases in the United Kingdom and undertook extensive research as to the advances in medicine and science since the 2003 trial.

Their efforts would equal hundreds of hours of slow, meticulous and highly valuable work for the application of a judicial review – and provide them with unique practical experience to complement their classroom learning.

‘Evidence’ doesn't add up

At the 2003 trial it was submitted there had not been such a similar case before, where three or more children from one family had died unexpectedly from natural causes or Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS). Yet that was untrue.

The Legal Centre and its law students unearthed vital research and literature concerning cases where there had been multiple reported deaths in the same family due to natural causes and SIDS.

“The UK cases of Sally Clark and Angela Cannings are two that stand out. Those cases were important because of the discredited expert Sir Roy Meadows,” Shaun said.

Discredited Meadows Law, named after UK paediatrician Sir Roy Meadows, referred to ‘one sudden infant death in a family is a tragedy, two is suspicious and three is murder, until proven otherwise’.

The cases in the UK were overturned.

“The students did quite a bit of research in terms of Meadow’s Law and why it was discredited,” Shaun said.

“And whilst in the trial, he (Sir Meadows) didn’t give evidence, and that mantra was not necessarily articulated in that way, it sort of pervaded the trial.”

A forensic pathologist engaged to review the medical evidence that had been presented at Kathleen’s trial, found there was no forensic evidence that any of the children had been killed.

Kathleen’s case shapes a young law career

For Newcastle family law solicitor Kate Wielinga, the Kathleen Folbigg case left a lasting impression on her, shaping her approach to her profession.

As a law student on placement at the Legal Centre in 2014, Kate recalls Shaun ‘pitching’ the case to students as one they could join and work on.

“Kathleen's case was quite complicated. But at its core, even though it was such a high level, such an interesting legal case, you’ve still got a family context,” Kate said.

“You’ve still got someone who was a mother, you've got someone who was in gaol, you've got an entire family grieving. And you've got, at its core, four children who died.

"In terms of my practise of law, it's been a salient lesson in always remembering that family context and what's at stake.

“I think working on Kathleen's case was a big reminder to always keep that front and centre.”

Diving into reviewing the case with an open mind, Kate found herself completely consumed by curiosity as to how, and why, Kathleen had been convicted.

Assigned the task of analysing research into cases where there'd been multiple instances of SIDS in a family, she soon realised Kathleen’s case had been purely circumstantial.

“There was no evidence of her doing something to the children that would hurt them. It was circumstantial in the fact that she had four children who died,” she said.

By this time, medical science was expanding rapidly.

At one point in time, it was believed a family who had lost one child to SIDS had no increased risk of losing another to SIDS. But science had begun to refute that proposition.

“Science had actually started to show that no, if you had one child die of SIDS, you're at a significantly increased risk of having another child die of SIDS,” Kate explained.

The ‘damning’ diaries

Despite being circumstantial evidence, Kathleen's controversial diaries had been viewed by some as a confession to harming her four children.

Renowned criminologist and forensic scientist, University of Newcastle’s Associate Professor Xanthe Mallett, has followed the Folbigg case closely. The Director of the University’s Justice Clinic, established in 2019, first encountered the case when writing her book Mothers Who Murder: And infamous miscarriages of justice. She raised the possibility Kathleen’s guilt couldn’t be proven beyond reasonable doubt in 2014, when it was unpopular to do so.

She says Kathleen’s diary entries were used against her.

“You've got to remember when Kathleen was writing her diary entries, she'd lost one, two, three and then four children. This is somebody in a heightened emotional state, psychologically, the entries are going to be incredibly traumatic.

“And when you take those little excerpts - and that's all that was presented in court to the jury, the prosecution chose the most suspicious looking parts - if you take them out of context, that to me was highly prejudicial, and extremely problematic.”

Pushing for the diaries to be reviewed by an expert, Shaun said a psychologist determined the entries were the innermost thoughts of a grieving mother expressing her feelings and emotions; and there were no admissions of guilt.

The day had come: The first inquiry

Together with the students’ research and new expert reports, the original medical evidence was challenged, arguing that it was misleading, unreliable and outdated.

In 2015, the Legal Centre, together with the barristers, submitted their application for a review of the convictions to the NSW State Governor.

It led to the first judicial inquiry in 2019, which considered new research and advances in medical science relevant to the causes of death of each child. It also considered new literature concerning the incidence of reported deaths of three or more infants in the same family, attributed to unidentified natural causes.

However, the inquiry, headed by former NSW District Court chief judge Reginald Blanch, KC, concluded the evidence as a whole, including Kathleen’s evidence in person about her diaries, reinforced her guilt.

It was a blow for all who had invested time, expertise and sheer determination to help a mother, who they argued, had been falsely accused and wrongly convicted.

Among the army of people working to free Kathleen was University of Newcastle alumna, Rhanee Rego, who was introduced to the case as a student on a university placement with the Newcastle barrister Robert Cavanagh. She later went on to be one of the lawyers representing Kathleen and continues to do so today.

Science takes time to catch up

Despite the devastating setback, the fight for justice wasn’t declared over.

New medical and scientific evidence came to light after the 2019 inquiry. It was discovered Kathleen’s daughters had a pathogenic genetic variant capable of causing cardiac arrest and death.

A group of independent scientists had studied the full genetic profile of all four children to establish whether there was anything that could have indicated they died an early death as a result of congenital genetic mutations.

“The science did take a little while to catch up,” Xanthe said, who has long campaigned for Kathleen, believing a justice process failed in her case.

“They were all listed as dying of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. That's just an umbrella category, which basically says, we don't really know why this child died.

“But we do know there are environmental, genetic and social factors which affect children and can lead to early death.”

Xanthe says Kathleen was prosecuted on the pattern of deaths.

“All four children dying, how extremely unusual this is in one family. It's not, but that was what was presented in court.

“If you can say, genetically, we can prove there's a reason the two girls died early, you have no pattern anymore and the whole house of cards falls over.

"But it took years for the science to really back up what some of us were saying. We were saying ‘there's no evidence – there was never any evidence’."

All or nothing: The second inquiry

In May 2022, NSW Attorney General Mark Speakman, ordered a second inquiry into Kathleen’s convictions, headed by former NSW Chief Justice Tom Bathurst, KC.

It was a breakthrough moment in the case - everything hung in the balance.

By May the same year the inquiry was underway, hearing the exonerating scientific evidence that a rare genetic variant may have been responsible for the deaths of Sarah and Laura Folbigg.

In addition, a senior paediatric neurologist told the inquiry Patrick likely died after an epileptic seizure.

Counsel assisting the inquiry submitted the evidence as a whole gave rise to reasonable doubt as to Kathleen’s guilt over the deaths of her four children. The DPP accepted the analysis of counsel assisting the inquiry.

To this day, Chief Justice Bathurst is yet to deliver his final findings.

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by The Australian (@the.australian)

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by 9News Queensland (@9newsqueensland)

The day of the pardon

With no hint of an unconditional pardon looming, and after serving 20 years behind bars, Kathleen Folbigg was released from gaol on June 5 this year.

On that day Shaun was supervising students sitting an exam in professional conduct. He remembers the exact moment well.

“It was completely unexpected. The expectation was Commissioner Bathurst would deliver his findings at some date,” he said.

“I’ve certainly reflected on it in terms of where this case started a decade previous. It was a real sense of relief that after this length of time, two inquiries, that the evidence had been properly considered and a decision made.

“But also, that the wheels of justice can turn very slowly.”

In the coming days many former students, including some based overseas, contacted Shaun to share their relief and recollections of their contribution to the case.

“As a teacher, I found it incredibly rewarding to think they had remembered so vividly their time at the centre, writing to me at length about their memories, their feelings and their experiences, so it's obviously a case that resonated with them and stayed with them.”

Kate has followed the case closely ever since she was involved.

“I was quite relieved to hear that effectively, justice had prevailed and that our legal system had a mechanism in it, and had demonstrated it had a mechanism in it, to correct mistakes that were made.”

Social justice warriors

During 2013-2017 when the Legal Centre represented Kathleen, multiple cohorts of law students worked on the case discovering the process painstaking work.

“They were particularly fired up because of the media reports about the case,” Shaun said. “Often, a lot of them are very passionate about righting wrongs and are particularly ignited by cases where there may have been a miscarriage of justice.”

Alumna Kate Wielinga says the opportunity to work on a high-profile case as a student in a regional area was a privilege.

“I think it was a unique opportunity, in the sense that as a junior solicitor, you just don't get the opportunity to participate in something that’s such a high level, high profile and complex matter.

“Particularly in a regional centre, to have such a prominent case wouldn't normally be available, especially as a junior. You're getting to see things you've seen as a law student, something similar to the cases you've read and getting to then compute that with the social context.”

Mitigating miscarriages of justice

How can such a tragedy be prevented from happening again?

Calls have been made to establish an independent Criminal Case Review Commission, such as those in England, Scotland, Norway, New Zealand and Canada.

The independent body would have powers to investigate criminal cases where people maintain they have been wrongfully convicted and could add a layer of transparency and accountability to the criminal justice process.

Despite the pardon and Kathleen’s release from custody, Kate says the pending findings of inquiry can't take away the miscarriage of justice that's occurred.

“It can't stop the fact that four gorgeous little babies died. It can't stop the fact that Kathleen has spent so long in gaol," Kate said.

“But it is a small amount of recognition, I suppose to undo a wrong but also to acknowledge that our justice system is robust enough that it can correct any mistakes that have been made along the way.

“And it can adapt to new scientific information, particularly in a context where that scientific information is in a stage of rapid discovery, which it was with the type of medical information that was relevant to Kathleen's children.”

Kathleen’s convictions will stand - unless the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal quashes them.

For now, Kathleen must wait. Again.

Legal Centre’s notable public interest cases

The Legal Centre and the School of Law and Justice take on major cases, which have significant public interest value. In each of these cases, the contributions made by law students are instrumental to the work being completed.

Wrongful detention of Cornelia Rau

The Legal Centre represented the family of Cornelia Rau at the inquiry into her wrongful detention at a Queensland prison and then at the Baxter Detention Centre.

Ronnie Levi Bondi Beach shooting

In 1997 NSW police shot dead French freelance photographer Ronnie Levi on Bondi Beach, while he was experiencing an episode of mental disturbance. The Legal Centre represented Mr Levi’s partner at the coronial inquest. As per the State Library of NSW: “A review of evidence undertaken by law students soon exposed the systemically flawed investigation of her husband’s death.”

Reinvestigation of Leigh Leigh murder

A reinvestigation by the NSW Crimes Commission of a case involving the murder of Newcastle teenager Leigh Leigh in 1989 was carried out following a 300-page submission from the Legal Centre. The submission identified failures in police methodologies and investigatory procedures. The matter was subsequently referred to the NSW Police Integrity Commission.

The University of Newcastle Justice Clinic

- In 2019, the University’s discipline of criminology joined the School of Law, Australia’s leading clinical law school, enabling even more intensive reviews of cases.

- The University of Newcastle Justice Clinic includes researchers and academics who work in collaboration with students to investigate cases for clients.

- The justice clinic is a hub to support people who have been impacted by issues within the criminal justice system; and aims to drive change to reduce issues in the future. It tries to assist where all appeal avenues have been exhausted such as miscarriages of justice and wrongful convictions; and also supports with misclassifications of death, missing persons and cold cases.

- Criminology and law students, as well as those from allied disciplines such as psychology, work on public interest cases in a work integrated learning context; dealing with real evidence, including police statements, court transcripts and post-mortem reports. The clinic provides students with deep learning opportunities to work with authorities, experts, and where appropriate speak with those directly impacted by the event.

* We acknowledge many more people than those mentioned in this story (at the University and beyond) were responsible for Kathleen Folbigg being freed. This story shares some of the background about the University of Newcastle's role in the early days of the movement and is just one part of an extraordinary story.